The following items related to Palau, the Marshall Islands and the Federated States of Micronesia are from the Asian Development Bank’s December 2019 “Pacific Economic Monitor.” The monitor provides an update of developments in Pacific economies. The articles were first published by the Asian Development Bank (www.adb.org).

Managing unconventional revenue streams: Marshall Islands and Federated States of Micronesia

Source: Federated States of Micronesia Fiscal Year 2018 Statistical Appendices

A 2005 corporate income tax law that allowed for the creation of a domicile in the FSM for companies operating overseas, followed by succeeding insurance legislation in 2006, created an attractive opportunity for foreign insurance companies. In particular, for captive insurance companies — subsidiaries that provide commercial insurance and business risk mitigation services for their parent companies and affiliates — of firms in Japan. These companies were able to reduce their effective corporate income tax from upwards of 40% in Japan (30% after recent tax reforms), to 21% in the FSM. A few overseas investment companies have also incorporated in the FSM since the enactment of the corporate income tax legislation.

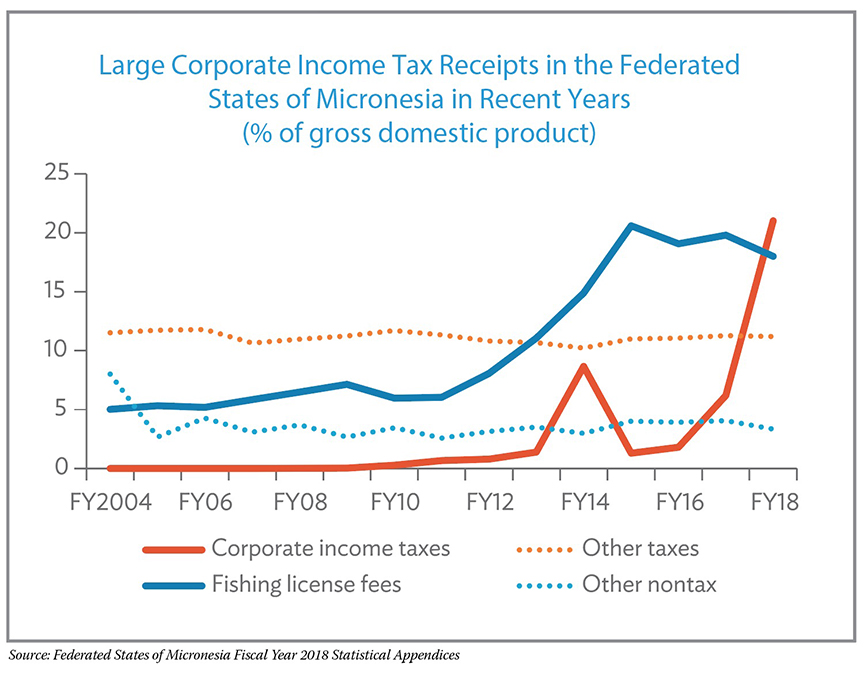

Revenue from corporate income taxation began in fiscal 2008 (ended Sept. 30, 2008 for both the FSM and the Marshall Islands) and averaged only $1.1 million, or equivalent to 0.4% of GDP, over the first five years of collection. Since then, collections have skyrocketed, averaging $24.9 million per annum during fiscal 2013 to fiscal 2018, the equivalent of 6.7% of GDP (Figure 8). This includes unusually large receipts — driven by windfall capital gains of domiciled companies — totaling $27.6 million (equivalent to 8.7% of GDP) in fiscal 2014; $22.7 million (6.2%) in fiscal 2017; and $84.5 million (21.0%) in fiscal 2018. In early fiscal 2019, corporate income tax collections already reached $48 million with receipt of another large payment. Swift legislation of tax transparency and information regulations reversed earlier issues of noncompliance with international standards. The FSM has been designated as “largely compliant” by the Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes.

Although recent large collections provide a welcome boost to the FSM’s fiscal coffers, the periodic nature of large one-off payments leads to high volatility in year-to-year collections, and can provide the impetus for increasing public expenditure in years when collections are much higher than anticipated During fiscal 2009 to fiscal 2018, corporate income tax collections, by far, were the most volatile source of government revenue, with a coefficient of variation — the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean — of 1.7, indicating high variance.

As with other income streams subject to large fluctuations, the utilization of corporate income tax collections can be smoothed by depositing higher revenues collected in years with large one-off payments into trust funds, for future drawdown during lean periods. Indeed, the national government recently adopted a policy of depositing 50% of annual corporate income tax revenues into the FSM Trust Fund. A follow-on policy likewise to deposit 20% of fishing license revenues, which have been boosted by a regional vessel day scheme for collecting fees from foreign fishing fleets, is now also in place. Refinements to the allocation formula, including possibly specifying a more dynamic and conservative fiscal rule that maximizes deposits while allowing for productive fiscal stimuli, would further promote sustainability and help control fluctuations in public spending. Given the public sector’s outsize impact on the FSM’s economic performance, a smoother public expenditure path, in turn, will contribute to curbing boom-and-bust cycles in GDP growth as well.

The Marshall Islands’ ship registry is an example of an open registry that allows the registration of foreign-owned vessels (as opposed to a traditional one that is only for ships owned and operated by nationals of that country). Ship owners choose a “flag state” based on factors such as regulatory environment, taxes, and quality of service offered by the registry (including safety records and presence in major ports). A registered vessel becomes subject to the laws of its flag state, which assumes responsibility — including ensuring safety at sea and compliance with international standards — for all vessels carrying its flag.

In the past three decades, the Marshall Islands’ registry grew from 39 vessels with a capacity of about 2 million gross tons to 4,627 vessels and almost 170 million gross tons, making the country one of the world’s leading flag states.

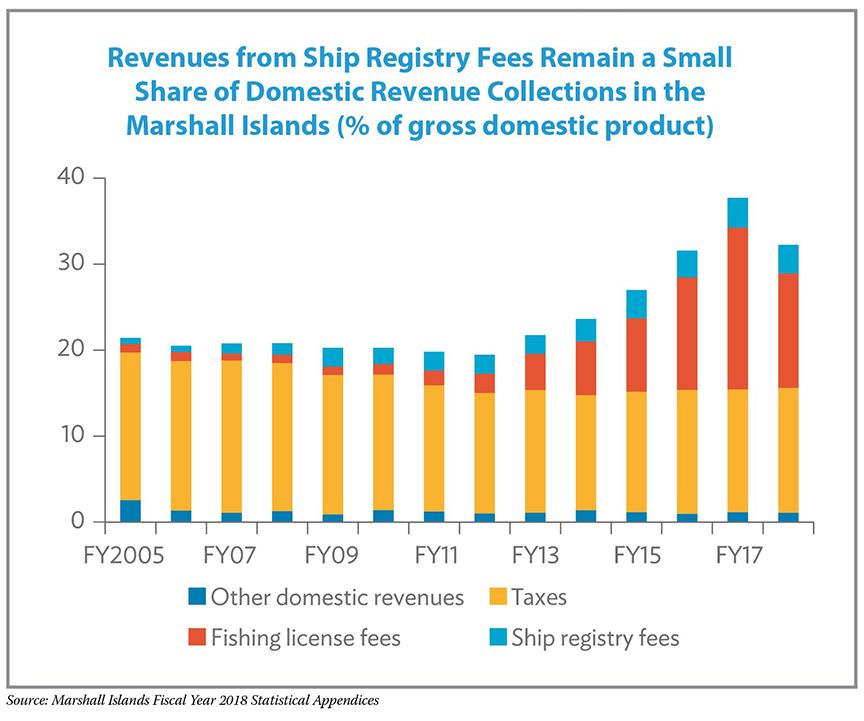

Like many other ship registries, the Marshall Islands’ registry is managed abroad; the United States-based International Registries, Inc. operates the country’s maritime as well as corporate registries through a wholly owned subsidiary, and every year a portion of its earnings goes to the Government of the Marshall Islands. The amount sent to the government has risen from $1.0 million (equivalent to 0.7% of GDP) in fiscal 2005 to $7.3 million (3.3% of GDP) in fiscal2018, declining only in fiscal 2010 following the global financial and economic crisis (Figure 10). However, revenues from fishing license fees have overtaken those from ship registry fees, especially since the regional VDS was implemented in 2012.

The government expects ship registry revenues to stay at about $7 million in the near term. Besides being an active member of the International Maritime Organization, the country enjoys “white list” status with the Paris and Tokyo memorandums of understanding, which seek to harmonize and uphold shipping standards, and has met the United States Coast Guard’s ship safety requirements for 15 consecutive years. Many newly built vessels have been choosing to register with the Marshall Islands.

The Marshall Islands ship registry is encouraging the registration of vessels certified by Green Award, a voluntary international scheme, as meeting standards that exceed industry regulations on safety, quality, and environmental performance. Aside from aligning with the country’s drive to adapt to climate change, this move also anticipates the International Maritime Organization’s cap on sulfur emissions from ships, which takes effect in 2020.

Although ship registry revenues account for a small share of domestic revenues compared with taxes and revenues from fishing license fees, domestic revenue collections, in general, will grow in importance unless the Marshall Islands’ Compact of Free Association with the United States is renewed before it and the attendant grants expire in 2023. In fiscal 2018, these accounted for 28.9% of total grants and were equivalent to 18.1% of GDP. Maintaining contributions to the Marshall Islands’ Compact Trust Fund, which is envisioned to offset the coming loss of the Compact grants remains of paramount importance. Together with state-owned enterprise reforms and other measures to manage public finances, this would help stabilize fiscal resources and public spending on essential services and growth-generating investment projects, even during leaner periods.

Source: Marshall Islands Fiscal Year 2018 Statistical Appendices

Improving the business environment in Palau

The private sector accounts for about 45% of the annual economic output in Palau, dominated by hotel and resort operators, restaurants, retail shops, and other businesses linked to the vital tourism sector. Although Palau’s private sector is among the largest — in proportion to the size of the economy — in the Pacific, substantial room for improvement remains in the current quality of its business environment. According to World Bank’s Doing Business 2020, Palau ranks 145th out of 190 economies surveyed, or at the bottom quartile of business enabling environments globally. Palau’s ranking has slipped gradually in recent years, with scores across Doing Business’ 10 key areas largely remaining stagnant since 2016, indicating a paucity of reforms related to private sector development.

Benchmarking Palau’s current scores with those of the two bestperforming Pacific economies — Samoa (ranked 98th) and Fiji (102nd) — offers some insight on specific areas for reform and improvement. Relative to these comparators, Palau rankings are particularly lower in three indicators: protecting minority investors, resolving insolvency, and getting electricity.

Addressing weaknesses in the first two areas will require reforms to expand and complete legal frameworks for corporations. In the area of protecting minority investors, for example, policies to ensure full disclosure of directors’ potential conflicts of interest; shareholders’ participation in electing and dismissing an external auditor; and possible avenues for minority shareholders to sue and hold interested directors liable for prejudicial-related-party transactions are missing currently. Similarly, no explicit measures are in place to disallow preferential or undervalued transactions in Palau’s insolvency framework at present. Closing these gaps in the legal framework, as demonstrated in comparator Pacific economies, can help reduce uncertainties and risks for potential private investors.

Palau’s low ranking in the getting electricity indicator reflects both the long time it takes for a business to acquire a new permanent connection — 125 days as opposed to an average of 63 days for East Asia and Pacific — as well as the poor quality of electricity services. These reflect longstanding inefficiencies in the operations of the Palau Public Utilities Corporation (PPUC), a state-owned enterprise providing electricity, water supply, and sanitation services. Currently, there is no independent regulator in place to monitor PPUC’s performance, resulting in Palau rating significantly much poorer than comparators in the reliability of electricity supply as measured, for example, by average service interruption frequencies and durations.

From a broader perspective, improving the performance of utilities perhaps is the key to unlocking further private sector development in Palau. Reform is underway in PPUC to move toward full cost recovery tariffs, particularly in water supply and sanitation services, and eliminate the need for subsidies and incentivize improvements in operational efficiency and services delivery.

Further, establishing an independent regulator — not only for electricity but also for other utilities, including those providing information and communication technology services — will help promote a level playing field that should encourage expanded private investment and induce better service quality and pricing for customers.

Exploring public–private partnerships to increase renewable energy generation capacity and stimulating market competition in retail information and communication technology services, can also help reduce tariffs and expand access to underserved areas over the longer term. In turn, improved access to and quality of basic services can underpin steady increases in broader business activity that should help revitalize Palau’s economy and reduce its exposure to volatilities stemming from international travel and tourism trend.