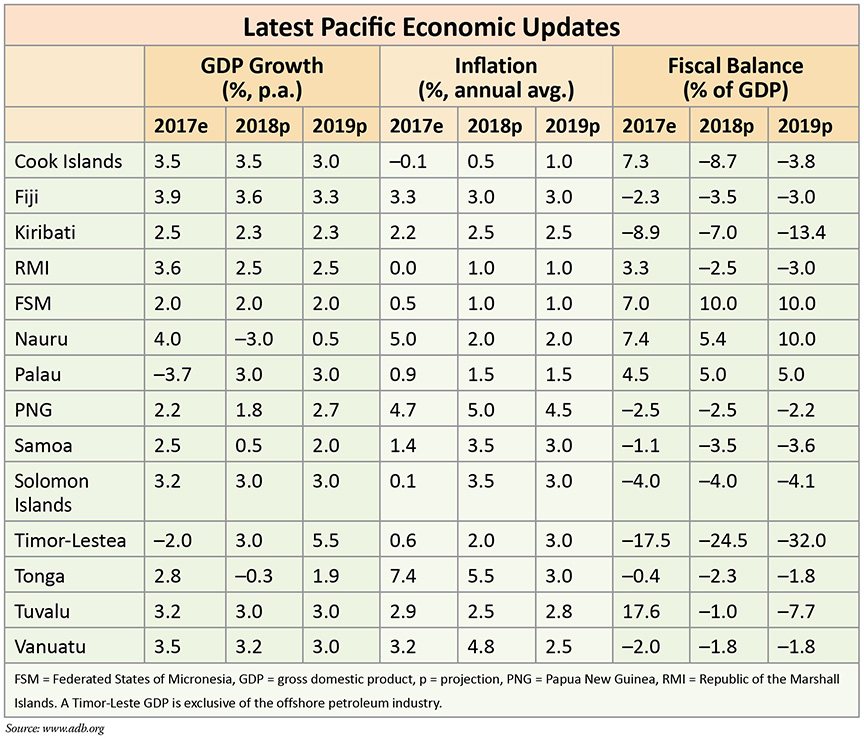

The following items on the Marshall Islands, Palau and the Federated States of Micronesia is from the Asian Development Bank’s “Pacific Economic Monitor” mid-year review issued in July. The monitor provides an update of developments in Pacific economies. The articles were first published by the Asian Development Bank (www.adb.org).

From a broad perspective, digital currencies are already part of the daily lives of most people in the Pacific. Their most common form — electronic money or e-money — is regularly used not only for e-commerce transactions but also as a more efficient and less costly means for overseas workers to remit money back home. While e-money is a digital representation of the value of legal tender (also known as fiat currency), other digital currencies are virtual currencies that are denominated in different units of account (e.g., frequent flyer miles, retailer rewards points and online game coins). Cryptocurrencies are a subset of virtual currencies that are characterized by two key features: full convertibility, including payment for goods and services or other virtual currencies; and decentralized systems for issuance, exchange and payments and settlements (as opposed to a “central bank”) underpinned by cryptography, which converts data into a secure format that is only accessible to participants. Decentralization is commonly operationalized through distributed ledger technology, where each transaction record is shared digitally and subjected to verification by a large peer-to-peer network.

A call back to Micronesian history

An early form of distributed ledgers was already in use in the North Pacific as early as 1,000 years ago, with the Rai, or stone money, of Yap in the Federated States of Micronesia. Rai derives value from being made of limestone, which is absent in Yap and, therefore, had to be quarried and transported from other islands, mostly Palau. All Yapese were free to import and produce additional units into the monetary system, with associated labor and transport costs acting as a check on rapid inflation (Berentsen and Schar 2018).

As stone discs measuring up to 3.6 meters in diameter, 0.5 meters thick and weighing up to 4,000 metric tons, the largest and most valuable Rai were difficult to physically exchange at every transaction. The Yapese instead just transferred ownership of the stones, regardless of its physical location. The system works as long as everyone on the island is eventually informed of all changes in ownership — a distributed ledger, subject to some communication lags — such that the owner of each stone is common knowledge. Any ownership conflict was settled collectively, which was possible given the relatively small size of and close relationships within the island community.

Cryptocurrency as money?

Recently, there were several attempts to introduce cryptocurrencies in the Pacific. In the Marshall Islands, a law passed in February 2018 paves the way for issuance of a cryptocurrency — the Sovereign, or SOV — to be recognized as a second legal tender in the country, in addition to the U.S. dollar. Another private company also offered to partner with the FSM to introduce the country’s own legal tender cryptocurrency, while Palau has received inquiries about potentially establishing a bank specifically catering to cryptocurrency transactions. Neither of the latter proposals has so far gained any traction.

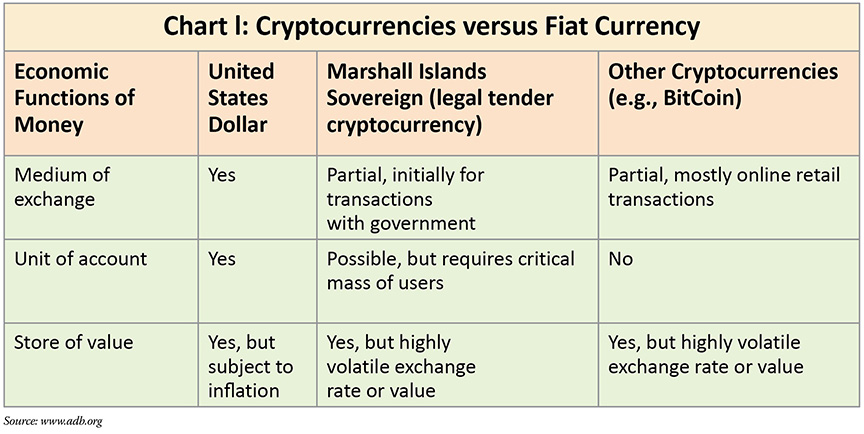

The Marshall Islands’s move to back the Sovereign as legal tender raises several important issues. First, it is unclear whether the Sovereign, or any cryptocurrency, can adequately fulfill any of the economic functions of money (see Chart I). Recent experience has shown that cryptocurrencies (e.g., Bitcoin) can be subject to large price volatility swings that limit their use as stores of value.

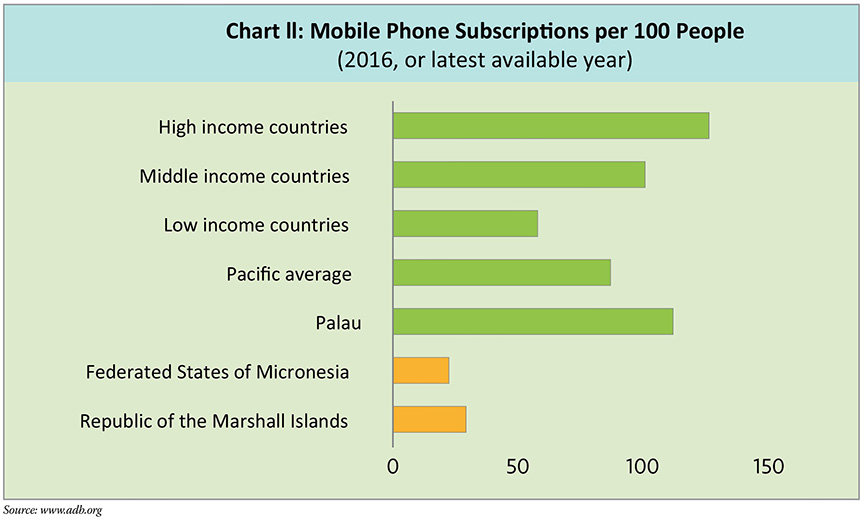

It remains unclear how initial issuance costs will be financed, but the government plans to issue 20% of its Sovereign allocations to residents. The cryptocurrency will immediately be accepted for settling debts and paying taxes and other public fees within the country, with hopes of facilitating its eventual use for other day-to-day transactions. Sovereign users would be required to identify themselves in transactions, moving away from the anonymity of conventional cryptocurrencies but enabling government regulation. However, regular use of the Sovereign as a medium of exchange and unit of account will depend heavily on people’s access to quality information and communication technology services. Unfortunately, this is an area where the Marshall Islands is clearly lagging, which will likely hinder the development of the Sovereign as day-to-day money (see Chart II).

More importantly, countries tend to decide to create their own domestic currencies based on their need and capacity to employ independent monetary and exchange rate policy toward ensuring macroeconomic stability. However, the Sovereign appears to be considered more as an investment opportunity to raise much needed government revenues. Banking on creating value from being the first cryptocurrency that, as legal tender, could bridge conversion between fiat and virtual currencies, the government and its private partner anticipate large proceeds from the initial coin offering. Rather optimistically, a windfall of almost six times the current domestic revenue generation is expected, plus a sharp appreciation in the value of tokens thereafter. The Marshall Islands already plans to split its share of the proceeds among climate change mitigation efforts, the national budget and Marshallese affected by nuclear testing.

However, realizing these windfall revenues depends on the eventual uptake of the Sovereign. Like other cryptocurrencies, the Sovereign’s value will be largely driven by expectations that other users will also adopt and use it. Some potential investors may ascribe additional value to the Sovereign being backed by the government, but this may be muted given risks associated with the Marshall Islands’s narrow resource base and economic vulnerability. If the Sovereign fails to reach a critical mass of investor-users, then the government, resident citizens and the private partner will be left with tokens of limited value. Further compounding the situation would be monetary and financial stability risks stemming from the introduction of the Sovereign as a fully convertible legal tender without the monetary and exchange rate policy framework, among others, to support the Sovereign’s integration into the mainstream economy.

Finally, the issuance of a legal tender cryptocurrency could further expose the Marshall Islands to possible money laundering and terrorism financing risks, as well as to cybersecurity attacks. Should the Sovereign become prone to use for criminal purposes, it may deteriorate into a liability for the Marshall Islands and its standing in the global financial community.

Financial access and inclusion

Although advancements in financial technology could revolutionize access to financial services, Pacific governments will be well advised to proceed with caution to avoid false starts with unproven ventures. Instead, focus should be on strengthening policy and institutional

frameworks that would help underpin steady improvements in financial access and inclusion, particularly in the North Pacific.

The FSM lags peers in terms of financial access and inclusion. Only about half of the population have deposit accounts. Its financial system comprises two commercial banks: one local (Bank of the Federated States of Micronesia) and a foreign bank (Bank of Guam), which combine for a total of eight branches and 10 ATMs. Despite the FSM’s geographical layout, there is no mobile banking service for those living in the outer islands. Further, the protracted implementation of land reform provides limited options for people who are unable to use their land properties, either as collaterals or to develop them for bankable projects.

Likewise, the banking system of the Marshall Islands comprises two commercial banks, but these maintain only five branches and two ATMs. The sector also has two large money transfer operators (MoneyGram and Western Union), two insurance companies, and a pension fund. The risk of losing the correspondent banking relationship between First Hawaiian Bank, a U.S. bank, and the Bank of the Marshall Islands, the Marshall Island’s only domestic commercial bank will not only adversely affect the economy but could disrupt cross-border payments and economic activity and weaken financial inclusion, particularly in the outer islands. Palau’s finance sector is dominated mainly by five commercial banks, two pension funds and a development bank. Booming tourism in the country has contributed to steady growth in deposits. However, the total number of depositors has declined from 2014 to 2016. The prevalence of asymmetric information, exacerbated by weak informational requirements of the prevailing tax system, makes it difficult for banks to assess the creditworthiness of potential borrowers.

Greater financial access and inclusion has been shown to have a positive impact on economic growth globally. In the North Pacific, the crucial role of banks and other intermediaries in mobilizing scarce financial resources has been hindered primarily by an inability to use land as collateral, as well as skills gaps in business development. Reforms allowing for long-term land leases and expanded use of secured transactions can help ease collateral constraints, while capacity development in basic financial literacy and business planning should help stimulate entrepreneurial activity. These will be crucial pieces toward solving the private sector development puzzle and put North Pacific economies in a better position to capitalize on opportunities afforded by digital financial solutions.