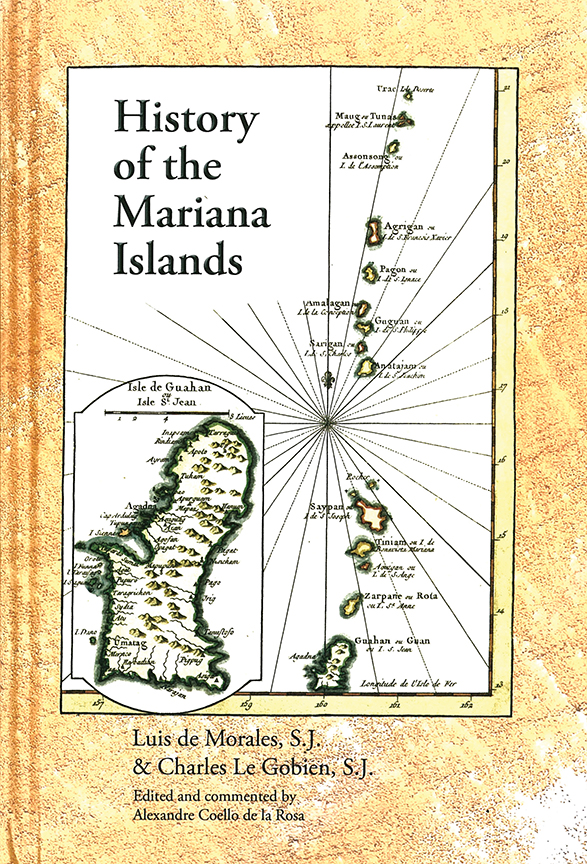

The attractively bound “History of the Mariana Islands” takes us back to the beginning of the 18th century and the publication in 1700 of a book about the Mariana Islands by a French Jesuit, Charles Le Gobien, at a time when Christianization of far-flung locations was funded by the Spanish monarchy.

The attractively bound “History of the Mariana Islands” takes us back to the beginning of the 18th century and the publication in 1700 of a book about the Mariana Islands by a French Jesuit, Charles Le Gobien, at a time when Christianization of far-flung locations was funded by the Spanish monarchy.

At the time, the Marianas were a lackluster star in the Jesuit firmament, only important to show through their example that the Jesuit missions were philanthropic rather than politic or income bearing. The Jesuits themselves were dealing with “the legitimacy of the Jesuit method of cultural adaptation” as a means of missionary work and the book was designed to show that “the Jesuits were martyrs of their faith with a genuinely universal apostolic vocation,” as the prologue says.

An earlier 17th century Spanish version of the book, attributed to Father Luis de Morales — one of the members of the first missionary expedition to the Marianas led by Luis de San Vitores, accounts for the dual authorship. Through later translation and the fact that the book relies on “relations” or accounts from the field written by Morales and other Jesuits, raises the “integrated narrative” that Le Gobien used, since he never visited the Marianas.

The sources are amply covered in the prologue and the introduction, providing some 80-plus pages of use to researchers and history students and, where relevant, including suggestions for further reading.

The rest of the 282 pages of this English version edited by Alexandre Coello de la Rosa, supported by his research and translated from the Spanish, include the meat of the book in chapters or “books” (with references along the way) and an index, as well as a list of military officers, governors, viceroys and governor generals of the Philippines.

Though written from the Jesuit perspective, and much given to the narration of the violence and uneasy relations that accompanied the evangelization of the Marianas, the book gives many details of the daily lives, beliefs and situation of the Chamorros on the various islands, particularly the bigger islands.

Physical details of Chamorros of the time, their diet and typical longevity are described. From the experiences of the 1680s narrated by Father Morales, the book details that Chamorros are “stronger and more robust than Europeans are and “of considerable height and proportionate bodies, even though they only eat roots, fruit and fish.” It goes on to say, “It is not uncommon for some of them to reach the age of 100 and the first year that the Gospel was preached to them more than 120 who were that age were baptized and they were as healthy and strong as if they had been in their 50s.”

The building of churches, intermarriage (also with Filipino solders that accompanied Spanish forces) and education in Spanish and Catholic ways hastened close relations and conversions – the primary aim of the various missions in the islands, aided also by the fact that the priests learned the local language.

Chamorros were “taught to dress properly and make clothing, to plant Indian wheat, to make bread and eat meat. Artisans were sent to various villages to teach them how to spin thread, sew, make cloth, prepare animal pelts, work iron, carve stone, build in the European manner and other trades necessary for life that were totally unknown to them.”

The introduction of the first horse to the Marianas in 1673 understandably “caused widespread surprise.”