The following on the Marshall Islands, Palau and the Federated States of Micronesia is from the Asian Development Bank’s “Pacific Economic Monitor” mid-year review issued in July. The monitor provides an update of developments in Pacific economies. The articles were first published by the Asian Development Bank (www.adb.org). — For previous notes on telecommunications developments in Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands and throughout the Pacific, see “Pivot point” in the July/August 2017 edition of Guam Business Magazine.

It is estimated that 75% of Pacific island countries, territories and states will be connected to submarine cables in the next 2 – 3 years. Past experience suggests that a submarine cable connection, when complemented by the right policies, could significantly increase internet capacity while also reducing costs to provide the service. This would facilitate economic integration not just for countries, but also for far-flung and isolated communities within countries that would be difficult to access by other means.

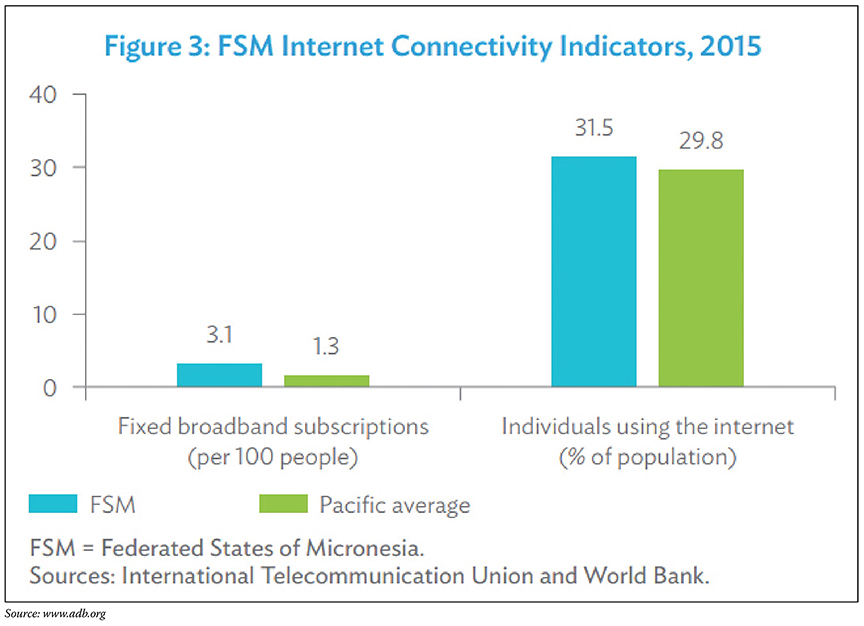

Communication gaps: internet connectivity regulation and competition in the North Pacific

Ongoing and planned efforts are expected to significantly expand the availability of faster, more affordable internet connectivity across the North Pacific economies of the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) and Palau. These include submarine cable links to all four component states of the FSM — Chuuk, Kosrae, Pohnpei and Yap — and Palau’s tourist-heavy domestic market, to go alongside existing connections to the Marshall Islands’ population centers and reforms to boost competition among ISPs.

Internet connectivity submarine cables in the North Pacific

Broadband internet connectivity through submarine cables first came to the North Pacific in 2010 through the HANTRU-1 system that connected Ebeye, Kwajalein and Majuro in the Marshall Islands, as well as Pohnpei in the FSM, to the Guam hub. Ongoing projects supported by ADB and the World Bank are soon expected to connect Palau and Yap through spurs and branching units from the Southeast Asia–United States system and Chuuk through Pohnpei. A proposed World Bank project to also connect Kosrae in the medium term is seen to complete the loop, fully linking the North Pacific economies with the global digital community through high-speed internet services.

Key issues

Although the Marshall Islands and Pohnpei were the first to be connected, available bandwidth capacity remained grossly underutilized due to high service fees stemming from monopolistic market structures and the cost of financing cable installation. In the Marshall Islands, the majority government-owned National Telecommunications Authority is the sole provider of internet connectivity services. NTA has consistently failed to generate sufficient revenues to finance repayment obligations for the HANTRU-1 loan, requiring government subsidies that have increased from $1.4 million — about 1.4% of recurrent expenditures — in fiscal 2013 (ended Sept. 30, 2013) to $1.9 million (2%) in fiscal 2015. Weak finances have also constrained NTA from pursuing further investments to improve services.

Efforts to improve the legal and regulatory framework for internet connectivity in the Marshall Islands have so far stalled. A World Bank budget support operation in 2013 aimed to facilitate the adoption of a new internet connectivity policy that would restructure the NTA and liberalize the sector. Similar reforms have been undertaken in other Pacific economies including Fiji, Kiribati and Tonga, with positive benefits in terms of healthy market competition and lowered prices. However, a combination of factors — including vested interests opposing internet connectivity sector reforms and capacity constraints that caused continuing lengthy delays in implementing complementary technical assistance — meant that the operation had limited success in achieving its key objectives.

The Marshall Islands experienced a near-blackout of internet services when its submarine cable connection was damaged toward the end of 2016. For three weeks, bandwidth was limited to what could be provided via satellite, which was only a small fraction of that usually supplied by the cable. Internet access was thus rationed, mostly among government offices and businesses and residential users were largely cut off from all but e-mail, even after the NTA purchased additional satellite bandwidth to help alleviate the situation.

In contrast, the FSM has made significant progress in paving the way for increased competition in internet connectivity services. The FSM Telecommunications Act of 2014 allows for the issuance of licenses to new ISPs, effectively introducing contestability to state-owned FSM Telecommunication Corp.’s monopoly position. The act also provides for the establishment of the Telecom Regulatory Authority — an independent regulator responsible for protecting consumers, issuing licenses and managing interconnections and critical infrastructure-sharing among potential competitors. Recent experience in other Pacific economies, including Fiji, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga and Vanuatu suggests that telecommunications liberalization that is accompanied by the introduction of appropriate institutions and market structures can successfully attract new entrants even in markets with small customer bases.

FSM Telecom Corp. has operated on generally sustainable financial footing, requiring little or no government subsidies while covering a relatively broad segment of the population. It recently introduced mobile broadband service in Pohnpei. However, internet service fees remain elevated, partly due to the costs associated with financing the Pohnpei cable and diseconomies of scale in servicing smaller, more remote areas through more expensive satellite connectivity. With broadband cable connections coming soon for Chuuk (the FSM’s most populous state), as well as Yap (the state with the highest income per capita), demand for faster and more reliable internet connectivity should pick up, particularly as service costs come down. A synergistic boost to demand can also be expected once Kosrae is likewise connected and the digital divide across the four states is fully closed, allowing for nationwide information sharing and transfer, for example, through integrated e-education, e-health and e-government systems. Rising demand could help attract new ISPs and soak up excess bandwidth capacity and increased competition should drive down costs and lead to significant gains in consumer welfare.

Palau’s relatively large tourism sector — with an annual tourist-to-resident ratio of about 8:1 — generates sufficient demand to allow space for as many as three ISPs to operate at the same time. These operators, however, effectively target disjointed market segments with no arrangements for technical or commercial interconnection. The state-owned Palau National Communications Corp., the largest ISP, mostly serves household customers through slow dial-up connections and more recently, mobile 3G data services. Palau Telecoms, a private provider, offers wireless broadband internet services mainly to government offices and business establishments such as hotels and resorts. Up until the indefinite suspension of its operations in July 2014, a second private provider — Palau Mobile Communications, a subsidiary of a mobile telecommunications company from Taipei, China — was also providing mobile 3G data services in major tourist areas and the Koror business district.

PNCC operates at full cost recovery. Although this effectively shields the government budget from the fiscal burden imposed by subsidies, Palau’s exclusive reliance on expensive satellite links has kept the cost of internet services very high relative to other Pacific economies. With the forthcoming availability of a high-speed submarine cable connection, Palau aims to reduce the cost of broadband (minimum of 256 kilobits per second) internet for consumers from the current rate of $650 per month to as low as $45.

Palau’s legal and regulatory framework for internet connectivity is incomplete, with gaps in oversight of network interconnection, wholesale and retail tariffs and broader competitive behavior. The government issued a national internet connectivity policy in 2013, which provides for the establishment of an independent internet connectivity regulatory authority. Independent regulation is seen to create a level playing field that will encourage more private investment and lead to improved service quality and more affordable pricing for customers. The independent internet connectivity regulator is expected to be in place by the end of 2017. The government is also reviewing a package of draft laws and regulations supporting procompetitive sector reforms outlined in the internet connectivity policy.

The Belau Submarine Cable Corp. is a state-owned enterprise created specifically to own and operate Palau’s new high-speed fiber-optic submarine cable system. BSCC’s inherent monopoly power over broadband capacity further highlights the need for strong regulation to ensure reasonable wholesale pricing and interconnection arrangements for retail service providers. The World Bank is currently providing technical assistance to support the operationalization of BSCC, including the preparation of a robust business plan and development of efficient operational arrangements to achieve least-cost provision of services. Although it will remain a majority government-owned corporation, BSCC is allowed by law to sell shares to private investors after the first 10 years of operation. Opening up BSCC to private sector participation is seen to encourage greater investment and maintain financially sound operations to ensure service quality over the longer term.

Next steps

As the North Pacific moves toward full broadband based connectivity, progress in strengthening internet connectivity regulation must be sustained to support greater competition, improve service quality and reduce costs. This should include fully functional and effective independent internet connectivity regulators in the FSM and Palau within the near term. In the Marshall Islands, efforts have been renewed to improve the NTA’s financial position and explore private sector participation toward strengthening the performance of the internet connectivity sector. The Marshall Islands government is also seeking to link internet connectivity sector development with its broader priorities, including reforms to public financial management and state-owned enterprises.

Efficient and reliable internet connectivity would help the North Pacific strengthen public financial management reforms by automating these functions, ensuring timely and accurate monitoring and reporting. It would also enable the North Pacific to work around the challenges posed by geographic distance. E-education and e-government would make use of internet connectivity to improve access — particularly for more remote communities — to education and skills training and frontline government services. Similarly, through e-health initiatives, internet connectivity would broaden access to medical information and help improve the overall quality of health care.

E-commerce would enable local firms to market niche products and services, including high-value tourism, which would also capitalize on the North Pacific’s remoteness by promoting natural, locally sourced ingredients and pristine locations and wildlife.

With complementary technical assistance and capacity building, improved connectivity could also open up internet connectivity-enabled services as another potential source of jobs, income and economic growth.