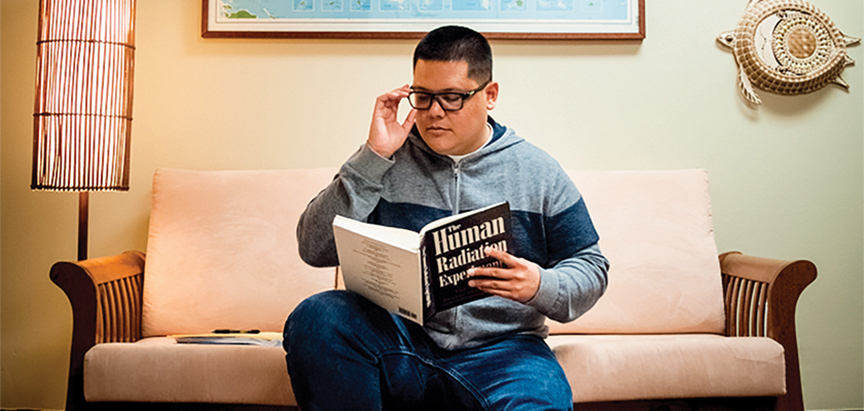

Julian J. Aguon

Founder, president and principal attorney

Blue Ocean Law

For human rights lawyer Julian J. Aguon, a Herculean effort was needed to hit the ground running on just about everything he does.

Aguon has been practicing law since 2009 and is licensed to work on Guam, Palau and the Marshall Islands. He is the founder, president and principal attorney of Blue Ocean Law, a firm devoted to representing and educating indigenous and non-self-governing communities at the international level.

He also is the 34th Guam Legislature’s legal counsel, and the lead litigator and special assistant to the attorney general of Guam in the notable Davis v. Guam case, which brings into question Guam’s political status plebiscite law.

With a mountain of responsibilities, the 35-year-old says he manages to do all of these things because he loves what he does.

“I’m very fortunate to do this work here,” Aguon says. “I could’ve taken other human rights posts in the mainland, but I didn’t want that life. I love this community and I’m happy to be here.”

Aguon says he has a great connection to the work he does because of his upbringing, having been born and raised on Guam and educated through the public school system. Growing up in a non-self-governing territory, Aguon says Guam shaped and formed how he sees the world.

Blue Ocean Law is the result of Aguon’s resolve. He took up the duty to assist indigenous people, whether they are awaiting self-determination or fighting to regain access to ancestral lands.

“We didn’t want human rights and saving the world to be an on-the-side thing. We want it to be at the forefront of what we do,” Aguon says. “We wanted a firm where the lion’s share of our work was committed to advancing the rights of vulnerable populations.”

His efforts for the indigenous people extend to the environment as well.

“Indigenous people live closest to the natural environment, and therefore they’re the first to really genuinely feel the effects and impacts of vandalism visible upon it,” Aguon says.

Education is an important component of his work, Aguon says, and his clients need to be informed of their civil rights so they can equip themselves with the tools necessary to protect what is theirs.

From an academic standpoint, Aguon is an adjunct professor at his alma mater, the University of Hawaii at Manoa William S. Richardson School of Law, and also a co-author of an extensive piece on deep-sea mining for the Harvard Environmental Law Review. The harms of deep-sea mining to Pacific islands are one of the bigger topics Aguon handles with his firm, and he collaborates with other attorneys and environmental experts throughout Oceania to gather information on it.

Blue Ocean Law has an internship program, approximately eight weeks long, which brings in students from prestigious schools including Harvard Law School, Yale Law School and Stanford Law School, Aguon says. He added that the interest from elite schools to his firm is a success for human rights and environmental law practice in the region.

There is no single type of person who can become a lawyer. In fact, the more diverse, the better, Aguon says. Some of the best lawyers he knows are English majors and mathematicians. Aguon himself studied women and gender in undergraduate school before heading to law school.

“For the law to be its best self, we need young people who are committed to principles of social and economic justice. People who want to restore the varied beauty of the world,” he says. “The best kind of law student is curious, rigorous and imaginative.”

Aguon hopes that Guam will have more human rights and social justice lawyers to serve the region. The indigenous and non-self-governing communities are best represented by individuals from those communities who understand their historical and cultural situation, he says.

“The law is a powerful tool in being able to uplift and empower oppressed communities.”